The Rabbit Hole of Rent Control

--

Landlords abandon markets. Developers stop building rentals. Apartment inventory drops. Resident mobility grinds to a halt. History, analysts and economists say that rent control will only worsen already bad housing shortages in those places with the greatest need for housing. Apartment owners don’t want it. Associations warn of its perils. In 1999, Forbes weighed in when it published, “The Dumbest Ideas of the Century,” citing the worst economic ideas of the 20th Century.

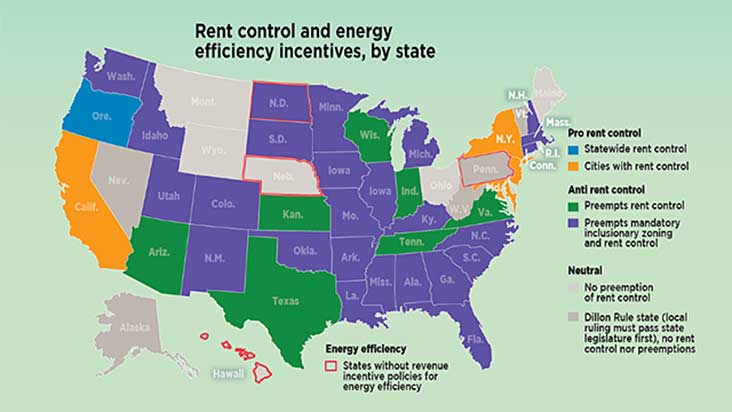

Why, then, did Oregon become the first state in the nation this year to pass statewide rent control? And—after failing at the ballot in 2018 with 60 percent voting against—why did tenants rights groups help introduce two rent control bills in the California legislature, where Governor Gavin Newsom has promised that the bills will become law? What’s a constituency to do?

Rent control refers to laws and ordinances that set artificial price controls on rent regardless of ownership, property profitability or market demand. It restricts the rights of property owners, limiting how they may operate their assets and often limiting the relief owners may seek from non-paying renters. In addition, rent control reduces the investment return and value of an impacted building, which is, in effect, a partial expropriation of private property.

Still, legislated rent control may be on its way in the Golden State. Demand has outstripped supply for years as California continues to create more jobs than its supply of housing can accommodate.

California’s renters are paying, on average, more than half of their incomes on housing as the state’s housing crisis intensifies. According to the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development, California needs to build 180,000 new homes annually through to 2025 to meet its growing housing demand. It’s created less than 80,000 annually in recent years.

For residents, the short supply of housing is felt in rising rents and rising taxes that span property, sales, gas, and other taxes in order to fund programs to reduce homelessness. At the same time, the construction of new shelters meets significant opposition.

The Golden State is home to 12 percent of the nation’s population and nearly half of the country’s unsheltered homeless. As homelessness rises, along with its accompanying health and logistical concerns, California legislators are looking for a quick fix. Maybe any quick fix to provide relief.

Landlords and developers are the first to advocate for building more housing. This would increase supply and naturally bring rents down. But apartment developers are faced with onerous building regulations, high land-use fees and municipalities that resist higher density and new building altogether.

Unintended consequences

California landlords may soon be faced with rent control, but also with related laws that reverse even the smallest progress toward conservation programs, like utility cost recovery programs and submetering, at a time when conservation of resources is most needed.

Utility cost recovery allows landlords to pass through utility charges to residents according to the residents’ consumption. The utilities potentially affected by RUBS (ratio utility billing) include electricity, natural gas, water, sewer, and waste management services. Utility cost recovery is effective in creating awareness of residents’ utility consumption and historically results in a reduction in utility use. Conservation, transparency, reassigning control of consumption back to the residents—it was a brief, albeit important, win. However, RUBS is now becoming the latest casualty in a quest to solve the housing crisis by reassigning costs to landlords.

San Jose prohibits RUBS in rent-controlled units

For years, tenants’ groups have fought at the California state level to ban RUBS and associated fees. Such a statewide ban was avoided in 2013.

However, last year when opponents of RUBS argued that its use created financial hardship on the residents of San Jose, California due to fluctuations in utility costs, the city council responded by enacting an ordinance prohibiting property owners from using RUBS. The ordinance was retroactive and voided existing RUBS agreements as of June 2018, although units built in San Jose after September 1979 are exempt.

The same ordinance limits other fees charged to residents, such as key replacement fees, NSF fees, late fees, and application screening fees.

Reversing the progress made in reducing the split incentive, where residents consume utilities but landlords pay for them, and decreasing consciousness among residents around conservation seems counterintuitive in a pro-environment state such as California. Financial relief for residents may come at a high long-term price for the drought-prone state.

The longest look back: NYC

New York City is the granddaddy of rent control, having had some form of the law since 1947. Nearly a million of the city’s units are rent-regulated, falling into one of two classifications: rent-controlled or rent-stabilized.

Built before 1947, rent-controlled apartments are occupied by residents who have likely had the unit passed down to the resident by family members since 1971. The landlords of these generational residents may charge no more than maximum base rent—a number that includes utility costs, property taxes, maintenance fees and return on investment. Landlords may raise rents every two years by no more than 7.5 percent. However, rent increases are subject to lengthy legal challenges by tenants.

New York City’s rent stabilization differs in that it impacts buildings of six or more units built between 1947 and 1974. In addition, landlords may opt into the rent stabilization program in exchange for tax benefits. Under this program, annual rent increases are set by New York’s Rent Guidelines Board, usually between one to three percent.

In June, New York Governor, Andrew Cuomo, signed a new and tougher rent control bill that shocked the real estate industry and made rent control permanent. New York building owners had removed over 300,000 apartments from rent regulation since 1994 through previous exceptions in the law. Nearly all exceptions have now been drastically limited or removed under the new legislation.

What lies ahead

Utility costs are among the most critical, albeit volatile, expenses for landlords and residents. Limited distributers and federal, state and local regulations only add to the complexity and cost of utility management and distribution.

Still, landlords remain the single largest distributors of utilities in the country. While an operational burden to landlords, utility management remains an attractive opportunity to increase conservation and also to control costs in the long run.

This article originally appeared in the Journal of Utility Management